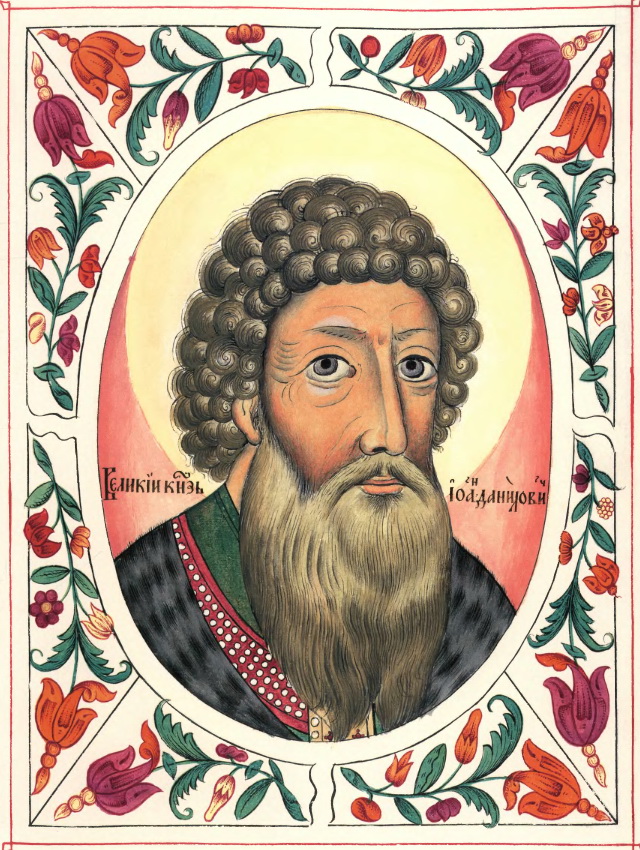

Ivan I of Moscow

Updated: Wikipedia source

Ivan I Danilovich Kalita (Russian: Иван I Данилович Калита, lit. 'money bag'; c. 1288 – 31 March 1340) was Prince of Moscow from 1325 and Grand Prince of Vladimir from 1331 until his death in 1340. Ivan inherited the Moscow principality following the death of his elder brother Yury. In 1327, following a popular uprising against Mongol rule in the neighboring principality of Tver, Ivan and Aleksandr of Suzdal were dispatched by Özbeg Khan of the Golden Horde to suppress the revolt and apprehend Aleksandr of Tver, who ultimately escaped. The following year, the khan divided the grand principality between Ivan and Aleksandr of Suzdal. Upon the death of the latter in 1331, Ivan became the sole grand prince. His heirs would continue to hold the title almost without interruption before the thrones of Vladimir and Moscow were permanently united in 1389. As the grand prince, Ivan was able to collect tribute from other Russian princes, allowing him to use the funds he acquired to develop Moscow. At the start of his reign, Ivan forged an alliance with Metropolitan Peter, head of the Russian Church, who then moved his primary residence to Moscow from the former capital, Vladimir. This decision would allow Moscow to become the spiritual center of Russian Orthodoxy. Peter was succeeded by Theognostus, who supported Moscow's rise and sanctioned the construction of additional stone churches in the city. Aleksandr of Tver was executed at the Horde in 1339, marking the end of a 35-year-long struggle between the princes of Moscow and Tver. Ivan died the following year and was succeeded by his son Simeon.